Introduction

The Minoan civilisation was an Aegean Bronze Age civilisation that arose and flourished on the island of Crete from around the 27th century BCE to the 15th century BCE. Rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century through the work of British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans, the Minoan art tells of a people who were keen observers of their world, in touch with the environment and enjoying the world they lived in.

The greatest collection of Minoan art is still on Crete in the museum at Heraklion, near Knossos. The world the art evokes is in some ways distant and strange and yet, at the same time, reassuringly recognisable and somehow modern.

However things are not what they seem: these famous icons are largely modern. Any keen observer at the museum can spot what survives of the original paintings amounts, in most cases, to no more than a few square inches. The rest of the painting is more or less a reconstruction, commissioned in the first half of the 20th century.

The difficulty lies in whether a reproduction can be counted as an example of the original. How much of the original needs to be present for the artefact to be considered a copy of the real thing?

The art of the fresco at Knossos

Archaeologists in the late 19th century had started to focus on early Ancient Greek sites. Heinrich Schliemann had discovered the tombs at Mycenae in 1876 and brought to life tales of King Agamemnon, his palace and gold. Many other archaeologists began to look for other sites twenty four years later Sir Arthur Evans began to excavate the site at Knossos on the island of Crete. This promised to yield a complex that would include a palace. He named the civilisation that had dwelt at Knossos the ‘Minoans’, after the mythical King Minos who is said to have held the throne there.

Numerous fragmentary wall paintings emerged from the excavations at Knossos. To make sense of these fragments Evans turned to Emile Gilliéron (1850-1924), who was later succeeded by his son Emile (1885–1939), as chief fresco restorers at Knossos where they worked for more than thirty years. They were recognised as the best archaeological illustrators working in Greece.

The frescoes at Knossos were especially exciting because they provided glimpses into the world of the Minoans. The first well-preserved image of the face of a Minoan to be discovered on one of the palace walls was that of the ’Cupbearer‘, which Gilliéron restored. It was clear this was part of a representation of a large procession decorating one of the main entrances to the palace. Evans decided to reconstruct the entrance and recreate the fresco, so the younger Gilliéron recreated more of the procession on a concrete superstructure reconstituted under Evans’ guidance.

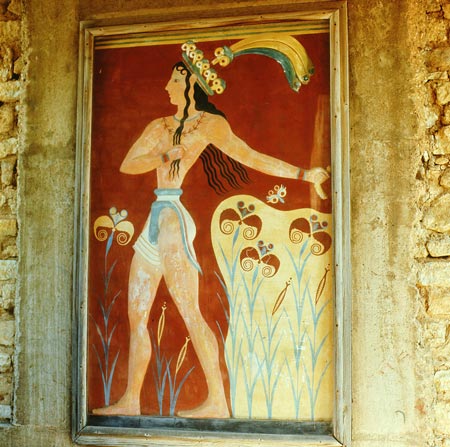

Gilliéron also restored the ’Prince of the Lilies’ in 1905 from fragments such as a small piece of the head and crown, part of the torso and a piece of the thigh see Figure 1. Records from the original excavation suggest the fragments were found in the same area of the ancient palace, but no face was ever found, and some have commented that it is not certain that all the fragments came from the same painting. Because the painting is a reconstruction from a limited number of fragments the overall picture appears awkward and there is no firm evidence that the subject was royalty.

Figure 1: Prince of the Lilies fresco.

© The Art Archive / Alamy

There is similar hint of controversy about the ’Ladies in blue’. It was first recreated by Gilliéron after the discovery of a few fragments, but that restoration was itself badly damaged in an earthquake.

One of the most important frescoes is the ’Priest King’ excavated in 1901 in the North-South corridor. The older Gilliéron worked on six fragments and in 1907 the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met), in New York, acquired copies of those fragments. Art historians at the Met pieced the fragments together to form a single relief. Later more fragments were found and Gilliéron made further restorations. A copy of this final restoration was placed where Evans thought the original would have been in the palace.

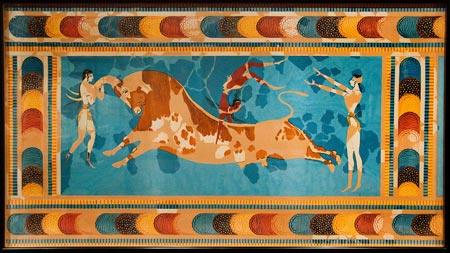

The well-known ’Bull Leapers’ fresco looks correct, but even here some have questioned the details of the border’s restoration. The original fragments of the top and bottom borders consist of overlapping variegated rock patterns between narrow bands with dentil patterns. However, there is no evidence supporting the rock pattern framing the sides, and it may be a modern addition.

Figure 2: The Bull Leapers fresco.

© Peter Horree / Alamy

Figure 3: Close detail of one of the bull leapers from the Bull Leapers Fresco.

© age fotostock Spain, S.L. / Alamy

So much excitement was aroused by the find at Knossos that the Gilliérons established a successful business selling reproductions of the antiquities from the Minoan and Mycenaean civilisations. These reproductions were sold around the world, inspiring other artists and writers like James Joyce (1882–1941) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973).

The restorations remain controversial because the remains are fragmentary and the original composition cannot be determined with certainty. But the Gilliéron restorations remain a clever solution to the problem of what they originally looked like in that it combines the existing pieces into a single figure.

The Artists

Emile Gilliéron (1850–1924) was born in Villeneuve, Switzerland. He studied art and trained in Munich and Paris before moving to Greece in 1876. In Greece he worked as archaeological illustrator for Heinrich Schliemann and other researchers became an art teacher and employed as drawing master to young members of the Greek royal family. One of his pupils was Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978) whose later paintings, such as Ariadne, drew on the mythology of Knossos.

The son trained at the Polytechnic in Athens and the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, before assisting his father at Knossos. He focused on the work of restoring the frescoes in the Heraklion Museum after the early excavations ended in 1913. He produced illustrations for Evans’ four-volume book, The Palace of Minos at Knossos, published between 1921 and 1936. The Greek Government appointed him ’Artist of all the Museums in Greece’, a position he held for 25 years, giving him access to many new archaeological finds.

Others artists were involved in the restoration, including Piet de Jong (1887–1967) who painted most of the ’Dolphin’ fresco in the 1920s.

Downloads

Restoration of Minoan paintings: imitation or reproduction?

PDF, Size 0.15 mb