Use this practical to produce copper from copper(II) carbonate, modelling the extraction of copper from malachite

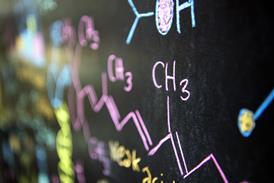

Malachite is a copper ore consisting mainly of basic copper(II) carbonate, CuCO3.Cu(OH)2. In this experiment, students learn how to produce copper from copper(II) carbonate by heating it to produce copper(II) oxide, which is then reduced to the metal using carbon as a reducing agent.

If possible, show the class a genuine sample of malachite ore and artefacts, such as paperweights or polished ‘eggs’ made from malachite, noting the green colour characteristic of many copper compounds. It contains copper, but how can copper metal be obtained from it? Heating will probably be suggested. This forms the first part of the experiment.

While the copper(II) oxide produced by heating cools down, discuss how to get the oxygen out of the oxide, leaving the metal itself. The discussion can be worked around to the idea of providing some element, carbon, which is ‘better’ at combining with oxygen than copper is. The ‘competition’ idea is illustrated by the second part of the experiment.

Explain that the green powder they start from is effectively powdered malachite, basic copper(II) carbonate.

The experiment should take about 20 minutes.

Equipment

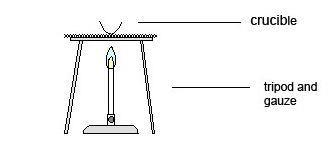

Apparatus

- Eye protection

- Crucible, preferably metal (see note 5 below)

- Crucible tongs

- Bunsen burner

- Heat resistant mat

- Tripod

- Gauze or pipeclay triangle (see note 6 below)

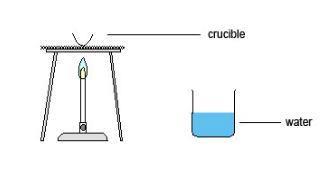

- Beaker, 250 cm3 or larger

- Spatula

Chemicals

- Copper(II) carbonate (HARMFUL), about 1 g

- Wood charcoal, powdered, about 2 g

Health, safety and technical notes

- Read our standard health and safety guidance.

- Wear eye protection throughout.

- Copper(II) carbonate, CuCO3.Cu(OH)2 (s), (HARMFUL) – see CLEAPSS Hazcard HC026.

- Powdered wood charcoal – see CLEAPSS Hazcard HC021.

- A metal crucible is best for this experiment as it is less likely to crack than a porcelain crucible.

- The gauze should preferably be one without a ceramic center. Such centers tend to prevent the crucible from getting hot enough. A pipeclay triangle may be used if the metal crucible fits snugly into it; pipeclay (or silica) triangles are intended for use with porcelain crucibles, metal crucibles tend to be larger and fit the triangles badly.

Procedure

Part 1

- Put one spatula measure of powdered malachite, copper(II) carbonate, into a crucible.

- Heat the crucible and contents, slowly at first, then strongly until there is no further change in appearance of the mixture.

- Allow the crucible and contents to cool for a few minutes.

Part 2

- Add two spatula measures of powdered charcoal (carbon) to the contents of the crucible. Mix with the spatula whilst holding the crucible with tongs. CARE: Grip the edge of the crucible with the tongs; do not attempt to grip around the body of the crucible because it is likely to slip out. Finally, add a thin layer of powdered charcoal over the surface of the mixture.

- Heat the crucible and its contents strongly on the tripod and gauze for a few minutes. Beware of sparks.

- Allow the mixture to cool for a couple of minutes.

- Half fill the beaker with water and then use tongs to tip the powder from the crucible into the water.

- Swirl the contents of the beaker around so that any copper falls to the bottom, and then pour off the water and charcoal suspension.

- Add more water and keep on pouring and swirling so only the heavy material is left at the bottom of the beaker.

Teaching notes

It should be clear from the outcome of part 1 that heating alone brings about some change but does not produce copper metal:

CuCO3(s) → CuO(s) + CO2(g)

(This is a simplification as copper(II) carbonate is, as mentioned above, actually a basic carbonate: CuCO3.Cu(OH)2. On heating the copper(II) hydroxide also decomposes, losing water, and ending up as copper(II) oxide as well).

Discussion of the nature of this change and the thinking behind the use of carbon also gives time for the crucible to cool somewhat so that manipulation at the beginning of part 2 is safer.

The purpose of the thin layer of charcoal on the surface of the mixture is to minimise the chance of the hot copper metal re-oxidising during the pouring-out process.

Additional information

This is a resource from the Practical Chemistry project, developed by the Nuffield Foundation and the Royal Society of Chemistry. This collection of over 200 practical activities demonstrates a wide range of chemical concepts and processes. Each activity contains comprehensive information for teachers and technicians, including full technical notes and step-by-step procedures. Practical Chemistry activities accompany Practical Physics and Practical Biology.

© Nuffield Foundation and the Royal Society of Chemistry

No comments yet