Bringing the story of chemistry to science museums

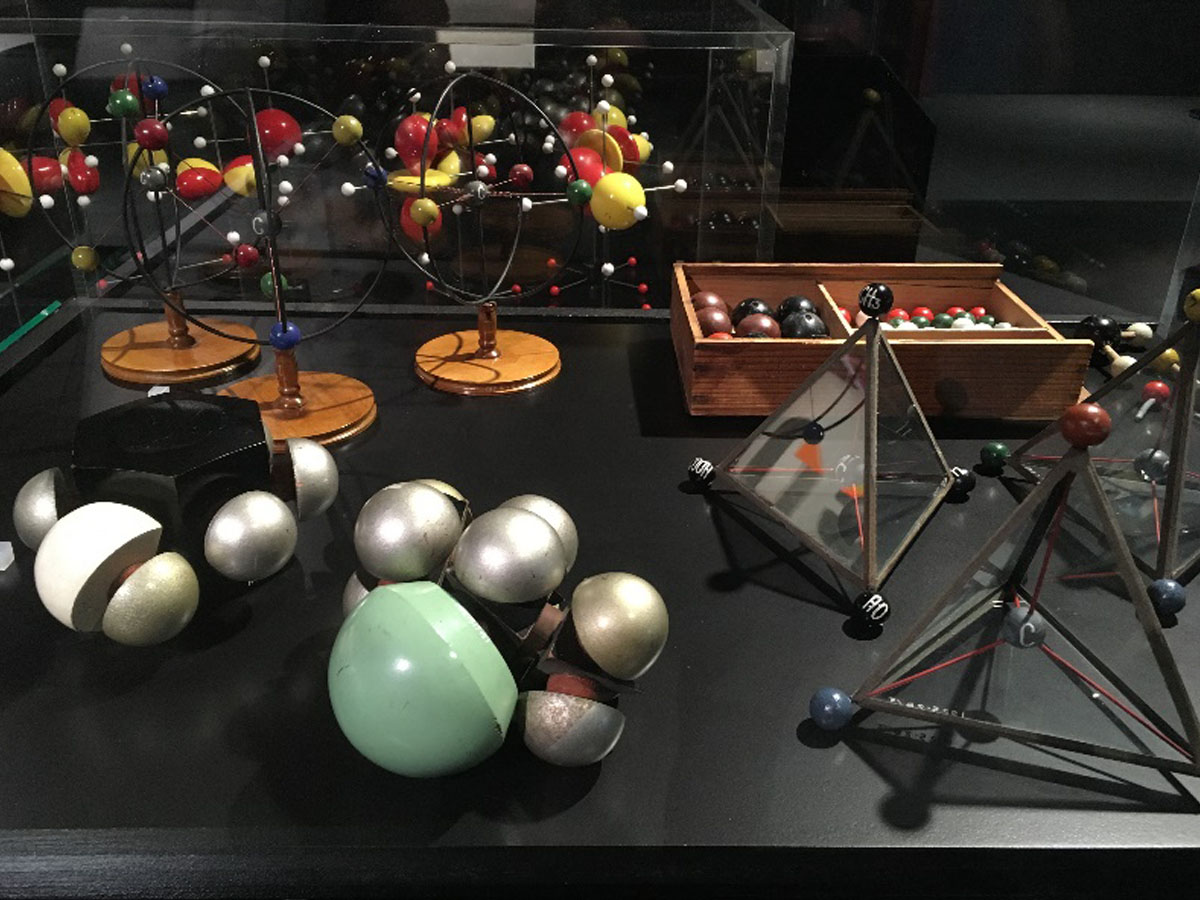

The exhibition includes atomic models to help visitors visualise the molecular structure of the materials. Picture: © Royal Society of Chemistry

Our Public Engagement Executive Dr Susan Vickers tells us about her recent visit to the Manchester Museum of Science and Industry, where she toured the new exhibition 'Wonder Materials: Graphene and Beyond'.

The chemical sciences are underrepresented in museums compared to the other major sciences. It’s not hard to understand why. It is challenging to develop stand-alone chemistry exhibitions that are safe, reproducible and will stand up to hundreds of little hands testing their durability in ways the designers probably didn’t imagine.

The new exhibition 'Wonder Materials: Graphene and Beyond' at the Manchester Museum of Science and Industry (MSI) is a brilliant example of incorporating chemistry into a science museum, and I was lucky enough to be able to see it last week. It was created at the museum, in partnership with the National Graphene Institute, and will be on display in this world premiere until June 2017.

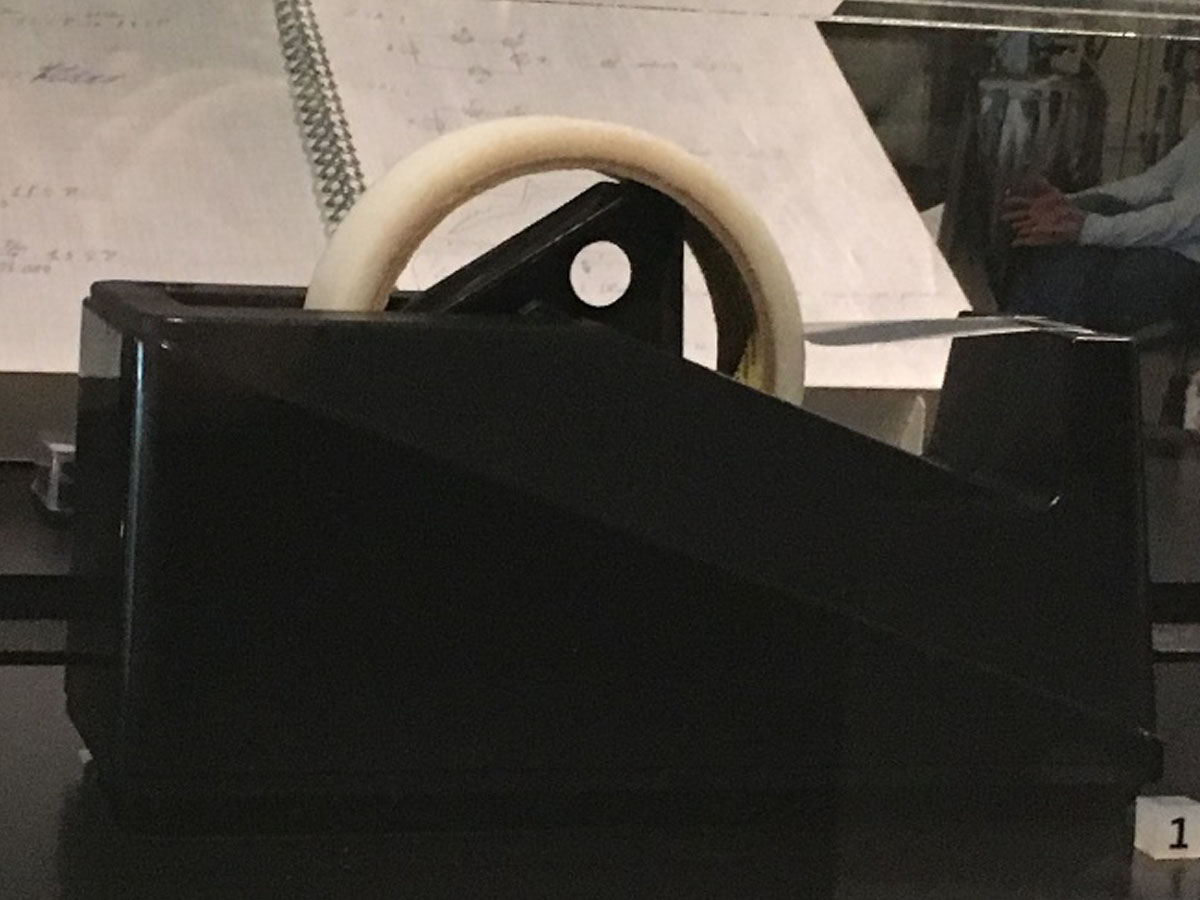

A simple roll of sticky tape demonstrates how graphene was discovered. Picture: © Royal Society of Chemistry

Graphene, along with nanomaterials in general, can be a fairly difficult concept to explain to a public audience. It can be tempting to talk about orbital hybridization, aromaticity or zero-gap semiconductors. These topics may be exciting to a chemical scientist, but are they exciting or even useful knowledge for a non-scientist? Maybe, but probably not. The story of graphene can be more tangible than this, even more human. Scientists working with graphene have interesting stories to tell, both inside and out of the lab, and the Wonder Materials exhibition aims to tell these stories.

Graphene was first extracted from bulk graphite using micromechanical cleavage, otherwise known as the Scotch tape technique. A Nobel Prize was awarded for essentially pulling apart pencil lead with sticky tape, and so I was delighted to see artefact number one: a roll of everyday sticky tape. It stands displayed beside a video discussing the discovery of graphene and a lab book from the early days of graphene research.

Lockers containing scientists' 'personal' items brought the stories to life. Picture: © Royal Society of Chemistry

As visitors move through the gallery they find profiles of scientists who work with graphene beside lockers containing 'personal' items; lab coats, lab glasses, and research equipment, as well as books, DVDs, music, sports equipment, and photographs. By including the hobbies of these scientists, the exhibition helps to dispel the common stereotype of chemical scientists as insular and unsociable. This section sacrifices some scientific content in order to humanise the work which, in my opinion, is completely justified.

The Wonder Materials exhibition doesn’t completely shy away from some more complex chemistry. There are atomic models on display – but even here the focus is on the story, artistry and history of the structure of graphene.

In a 'hands-on' area, visitors can build models of graphene, translating the nanoscale world into something than can be touched and manipulated. At the end of the exhibition, visitors can write and display their own ideas for ways in which graphene could be used in the future. While the suggestions may not all be realistic, it gives people the chance to have an opinion and apply the things they learned in the gallery.

The chemistry that is commonly in science museums takes the form of supervised hands-on demonstrations or stage shows, both of which require a lot more staff than most museums can regularly provide and rarely focus on recent advances in the chemical sciences or on chemical scientists themselves. It is important to increase the quality and quantity of chemistry in science museums to engage the public and increase curiosity about the chemical sciences. Developing multidisciplinary exhibitions that tell the stories behind scientific discoveries involving chemistry is one way to do this, and I think Wonder Materials: Graphene and Beyond is a brilliant example.