Curiosity: the fuel for discovery

Prizes and awards series

In the second of our series, we explore the importance of fundamental research, through the eyes of some of our 2020 prize and award winners.

Novel breakthroughs and transformative ideas are made possible through fundamental (also known as curiosity-driven) research. From the discovery of materials like Kevlar to therapies like Penicillin, the long-term impact of fundamental research on society is immeasurable.

Within the chemical sciences community, new discoveries are happening all the time, many of which we recognise through our Prizes and Awards programme.

While its contribution to society is unquestionable, curiosity-driven research is vulnerable to short-term thinking. The lag between research and the realisation of its practical application(s) can span 10, 20 years or more. The importance of curiosity-driven research can therefore get overlooked by policymakers and funders.

94% of respondents to our Science Horizons survey said that funding for curiosity-driven research is important for the advancement of the chemical sciences. It’s a message that we, the Royal Society of Chemistry, continue to uphold and promote.

With that in mind, we wanted to showcase some of the ways in which fundamental research is advancing the chemical sciences.

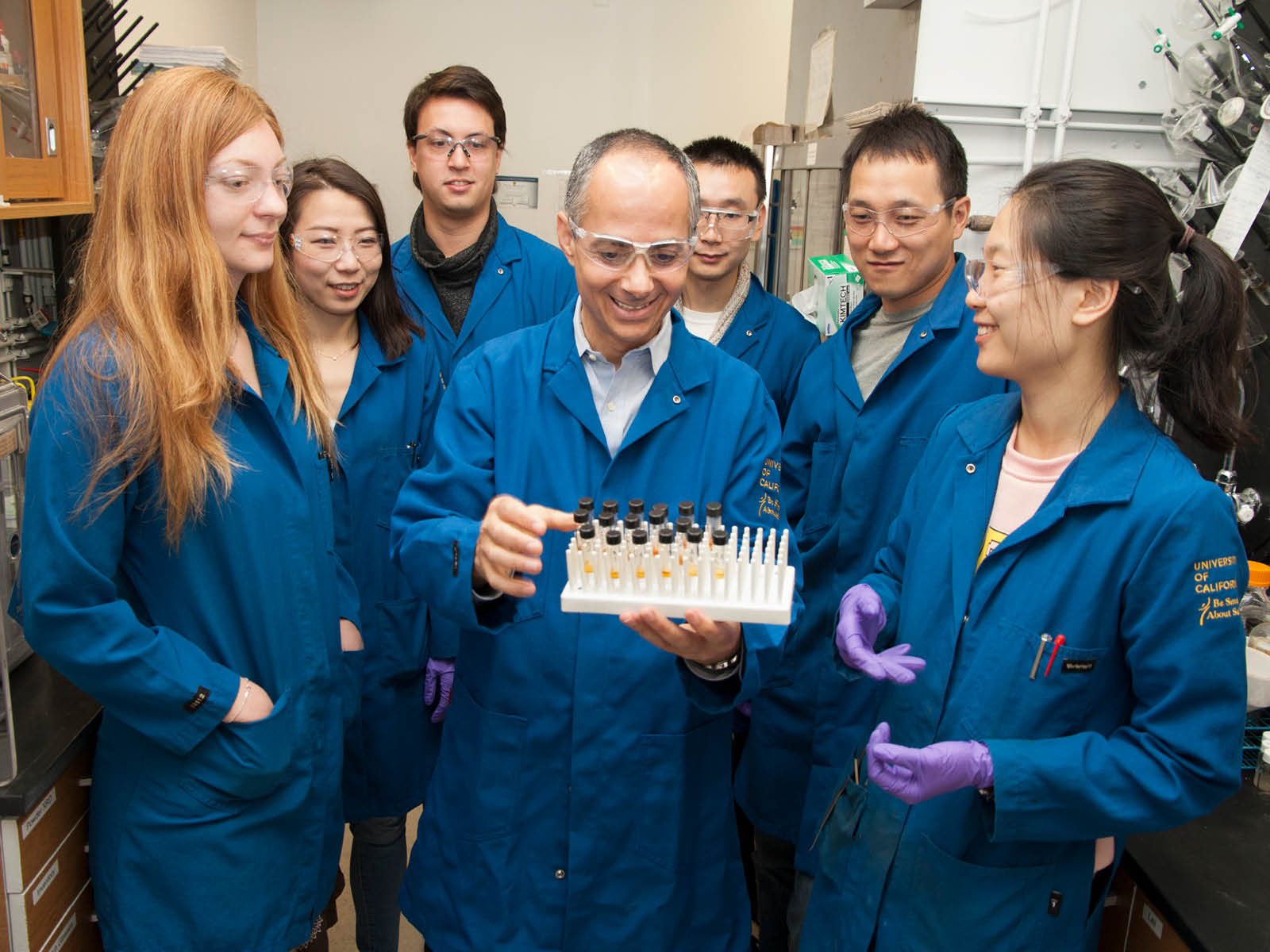

Professor Omar Yaghi, winner of the 2020 Sustainable Water Award, never set out to tackle water scarcity. Picture:

Combating water scarcity

Harvesting pure water from desert air is the pioneering work of Omar Yaghi, the James and Neeltje Tretter chair professor of chemistry at the University of California in Berkley.

Omar has established a new branch of science called reticular chemistry, resulting in porous materials called Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs). His ground-breaking technology using MOFs to harvest pure water from the desert air earned him the 2020 Sustainable Water Award.

"Discovery follows no blueprint or set path," says Omar. "Ultimately, a discovery can change our thinking, surroundings and society for the better in the shortest time than any other human activity."

"Everyone, young or old, is stimulated by good questions. They can be on the basic science level or they can be on a practical level. The mind is hungry for stimulation," he says.

Omar didn’t set out to tackle water scarcity though. "I was really more intrigued with the question of could I develop chemistry where I can use the infinite number of molecular building blocks that exist as my starting materials and stitch them together into chemical structures?"

"My motivation wasn’t necessarily directly to save humankind through carbon capture or water harvesting, but I knew very well that if I succeeded in answering that basic question that there would be many interesting and fascinating applications leading to solutions to some big problems in society."

Professor Madhavi Krishnan received the 2020 Corday-Morgan Prize for her research, which looks at fundamental ideas. Picture:

A new approach to diagnosing disease

"One of the feelings I love most about science is that any given day could be the one on which you make a discovery or gain some startling new insight," says Madhavi Krishnan, associate professor of physical and theoretical chemistry at the University of Oxford.

Madhavi’s research group’s interest lies in the control, manipulation, measurement and understanding of matter at the nanometer scale. This year, she received the Corday-Morgan prize for inventing a method of trapping molecules to measure the electrical charge of a single biomolecule in solution with high precision. The potential application of this new approach is the diagnosis and detection of disease.

"I enjoy the opportunity to explore the unknown, and in the process to create knowledge, as well as new technologies. It is one of the most gratifying feelings to chance upon a phenomenon in the lab, or come up with an explanation for an observation, of which we didn’t have a clue 'the day before'."

Clean, cheap energy for all

The demand for energy is rising rapidly due to population and economic growth. Energy already accounts for around 60% of total global greenhouse gas emissions. And while globally we’re making progress in finding cleaner ways to produce electricity, fossil fuels are the main source.

At the same time, the electrification of rural communities across the world is improving. However, 840 million people (predominantly in sub-Saharan Africa) still don’t have access to electricity at all.

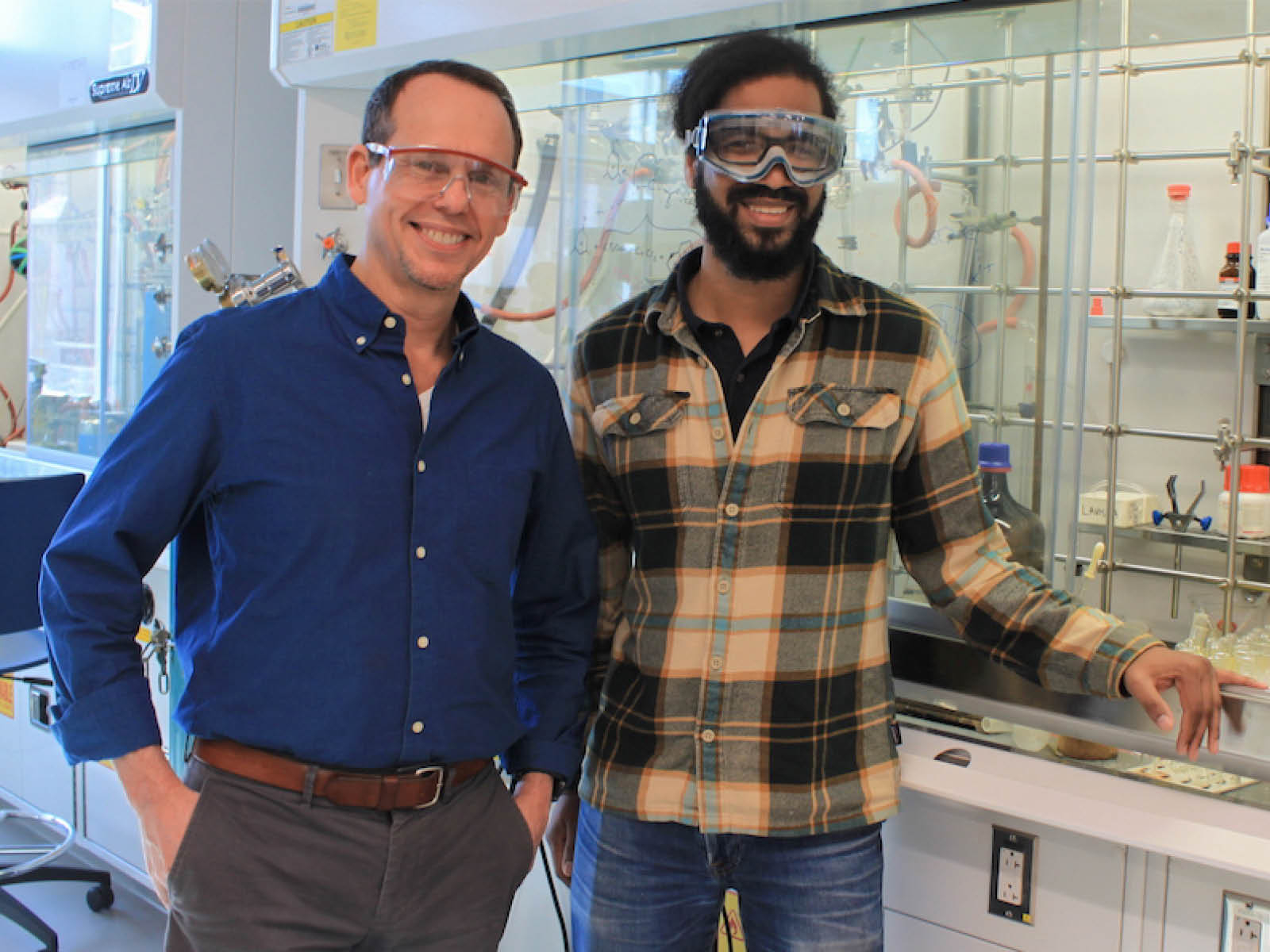

Professor Alan Goldman (left) carries out fundamental science that relates to large challenges facing society. Picture:

It is challenges like these that underpin Professor Alan Goldman’s interest in the development of organometallic catalysts and organometallic mechanisms. Based at Rutgers University in New Jersey, Alan’s contribution to this field of chemistry earned him the 2020 Sir Geoffrey Wilkinson Award.

"I try to do science that is fundamental but related to large challenges facing society, particularly the goal of transitioning to a prosperous environmentally sustainable economy; for example the development of carbon-neutral systems for transportation fuels and fertilizers."

Unexpected discoveries come from curiosity-driven research. In 1990 professor Goldman reported the development and the unanticipated mechanism of a novel photochemical system for alkane dehydrogenation. His group then went on to develop the first highly efficient thermochemical catalysts for alkane transfer-dehydrogenation.

"I try to do science that is fundamental but related to large challenges facing society, particularly the goal of transitioning to a prosperous environmentally sustainable economy; for example the development of carbon-neutral systems for transportation fuels and fertilizers."

Unexpected discoveries come from curiosity-driven research. In 1990 professor Goldman reported the development and the unanticipated mechanism of a novel photochemical system for alkane dehydrogenation. His group then went on to develop the first highly efficient thermochemical catalysts for alkane transfer-dehydrogenation.

The idea of scientific discovery captivated Alan at a young age and has never wavered.

"I first became interested in chemistry as soon as I got into a research lab and experienced the thrill of trying to discover something that no one before me had ever known or done. It’s still almost hard to believe I am lucky enough to get paid to do that."

Curiosity-driven research feeds the gaps in our knowledge of how the world around us works. It’s the bedrock for developing future solutions to global challenges.

It’s fundamental, but not basic.

Explore more…

- Visit our Prizes and Awards winners gallery to find out more about the people and the discoveries behind them.

- Download Science Horizons, our report on the emerging trends and priorities in scientific research.

- Find out how we are re-thinking recognition to make our science prizes fit for the modern world.