Journey of discovery

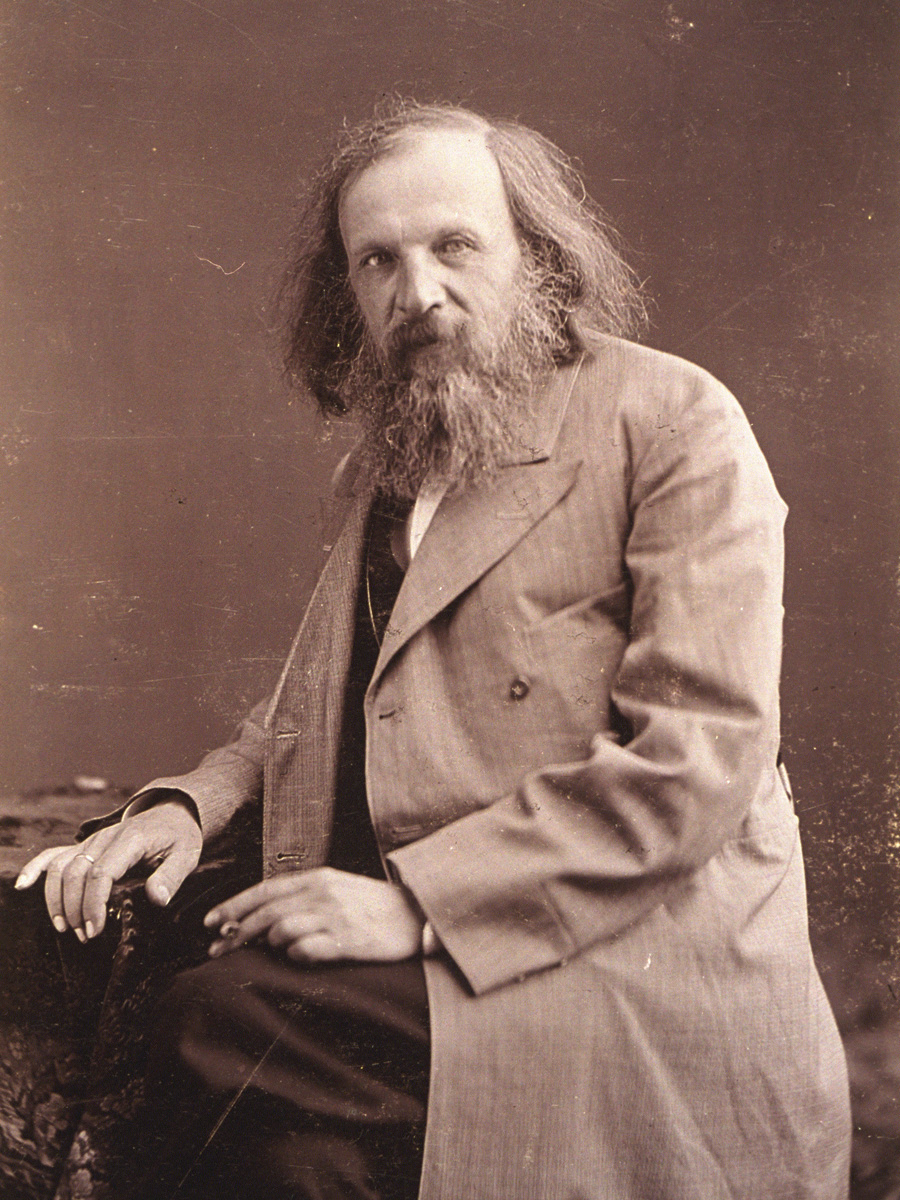

Picture: © Royal Society of Chemistry

Dmitri Mendeleev is known as the father of the periodic table, but his interests were wide-ranging and sometimes eccentric. We take a look at his varied and often tumultuous life.

Dmitri Mendeleev’s early life was not easy. Born in a Siberian village in 1834, the youngest of around 14 children (the exact number is disputed), his family was rendered destitute by a succession of disasters.

His father, Ivan, lost his sight and was unable to work so his mother, Maria, restarted her family’s abandoned glass factory in order to provide for the family. But by the time Dmitri was 13 his father had died and the glass factory was destroyed by fire.

Despite the family’s now precarious financial position, Maria recognised young Dmitri’s academic potential and decided to make his education a priority. She went to Moscow, taking Dmitri and two of his siblings with her, a formidable voyage of over 2,000 kilometres, made all the more intrepid by the limited transport infrastructure of the time. Unfortunately, when they arrived, the university in Moscow refused to accept Mendeleev because of his Siberian heritage.

The family moved on to St Petersburg, where he was accepted by the Main Pedagogical Institute – a former teacher training seminary that had become a fully-fledged university. Soon afterwards, tragedy struck again. Maria and Dmitri’s sister died of tuberculosis, and Dmitri himself became ill from the disease.

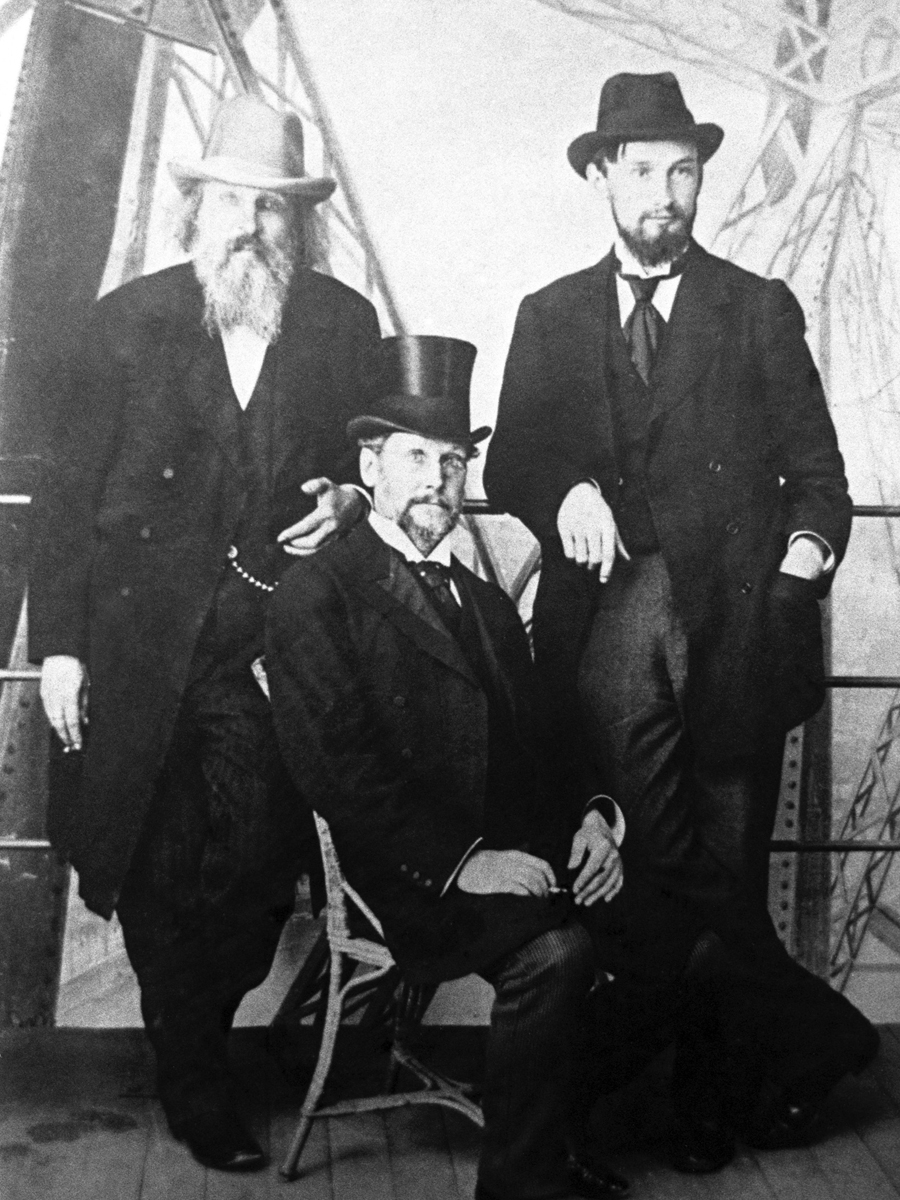

Dmitri Mendeleev (left) on the Eiffel Tower in September 1895 Picture: © Science Photo Library

In 1855, Mendeleev, now 21, took a post as a science teacher at Simferopol School on the Crimean peninsula, where it was hoped that the warmer climate would help him to recover his health. But within a week the Crimean War had begun, British troops landed on the coast, and the school was forced to close. He was transferred to another school in Odessa, further north, and eventually returned to St Petersburg where he spent two years carrying out doctoral research into the interaction of alcohols with water.

He dedicated his doctoral research to his mother:"Conducting a factory, she educated me by her own word, she instructed by example, corrected with love, and to give me the cause of science she left Siberia with me, spending thus her last resources and strength. When dying she said 'Be careful of illusion; work, search for divine and scientific truth.'"

Dmitri went on to work in Germany, where he attended the Karlsruhe Congress in 1860, the first ever international chemistry conference. The congress was attended by such chemistry legends as August Kekulé, Robert Bunsen, and Michael Faraday, and its main aim was to establish ways of standardising chemistry, a pressing need at the time. As a result of the congress the chemistry community adopted a unified system of assigning atomic weights, something that would later enable the modern version of the periodic table to come into being.

Mendeleev returned to St Petersburg in 1861, worried that Russia was trailing behind Germany in the science of chemistry. He set about trying to rectify the situation, laying out everything he knew in a 500 page Russian-language textbook, Organic Chemistry. He was still only 27 years old.

Discovering the periodic table

He was known as a charismatic teacher and lecturer, and held a series of academic and teaching positions throughout the 1860s. Meanwhile, he continued his research. He kept a collection of cards, each of which contained data on a different element. On 17 February 1869, while arranging his cards in order of atomic weight, he suddenly noticed a repeating pattern, whereby elements with similar properties would appear at regular intervals. He had discovered the phenomenon of periodicity, and it was this discovery that led to the formation of the periodic table we know and use today.

Diverse interests

While Mendeleev is best known for his work on the periodic table, in fact his career is notable for the diversity of his interests. Much of his work was very practical and applied, and he attempted to improve the efficiency of various industries. He was the first to suggest the idea of using pipelines to transport fuel, and he helped build Russia’s first oil refinery. He also tested fertilisers on his own property, and advocated for fertilisers to be used more widely in agriculture.

He wanted to bring scientific knowledge to the common people of Russia, and travelled around the countryside by train – in third class – meeting with peasants and offering scientific advice on their day to day problems such as manuring strategies.table we know and use today.

Mendeleev helped build the world's first Arctic icebreaker, the Yermak Picture: Image courtesy of Wikipedia

Suitcases, ships and balloons

Mendeleev was fascinated with shipbuilding and Arctic Maritime navigation, and he wrote over 40 scientific papers on the subject. His expertise led him to be involved in the design and construction of the world’s first Arctic icebreaker, the Yermak, launched by the Imperial Russian Navy in 1898. He worked with the Russian navy on other matters too – developing his own formula for smokeless gunpowder at their request.

In 1887 he made a solo ascent in a hot-air balloon, in an attempt to observe a solar eclipse, even though he had never flown a balloon before and had no idea how to land it.

Other achievements included introducing the metric system in Russia, defining the critical temperature of a gas, and determining the nature of solutions.

He made a solo ascent in a hot-air balloon Picture: © Getty Images

He was also a keen traveller, photographer and collector, and was even known as an excellent manufacturer of luggage. He put his suitcases together using a special bonding glue that he discovered himself whilst researching adhesive substances.

In 1862 Dmitri – under pressure from his sister – married a woman named Feozva Leshcheva, and they had two children together, Vladimir and Olga. It was not a happy marriage, with Dmitri prioritising his work in St Petersburg, and his wife living mainly alone with the children, 400 miles away near Moscow.

In 1880, when Dmitri was 46, he met and fell in love with 19 year-old music student Anna Popova. He became obsessed with her, proposed to her, and threatened suicide if she refused. He then asked his now estranged wife for a divorce. In Orthodox Russia divorce was complicated and heavily frowned upon, and even after the marriage was terminated the church forbade Mendeleev from marrying again for another six years. He ignored the ruling and married Anna anyway, causing huge scandal and public uproar. Anna and Dmitri had four children, including twins.

Academic controversy

His academic life was marked by some controversy as well. He was suspicious of certain scientific theories, such as the concept of electrolytes, he denied the existence of electrons, and when radioactivity was discovered in the 1890s, Mendeleev refused to accept the theory – seeing it as a threat to his own theory of the elements as individual entities.

Ironically, element number 101, which is named mendelevium after him, is highly radioactive. It was discovered by Albert Ghiorso, Glenn Seaborg, and their team at the University of California Berkeley, in 1955, 48 years after his death. They produced the highly radioactive element by bombarding an isotope of Einsteinium with alpha particles.

Mendeleev died from influenza in 1907, just short of his 73rd birthday. He was buried near his mother in Volkova cemetery at St Petersburg. He had a State funeral, at which students carried a periodic table aloft.