Week 12: Can you help us with #Chemglass?

Sophie Waring is Chemistry Curator at the Science Museum Picture: © Royal Society of Chemistry

Sophie Waring is Curator of Chemistry at the Science Museum, and she needs your help.

The Science Museum has a vast collection of historical glassware, and while much of it is well documented, in some cases they have very limited information about who owned it or what they used it for, which is where our members come in.

Some of the items in the collection were in use until relatively recently, and whilst we may know broadly what their purpose was, Sophie would like to know more about their practical application – what kind of experiments they would be used for, or how they worked.

If you were studying chemistry a few decades ago you might remember using some of this glassware, or you might have glassware in your lab today that looks similar, or has a similar purpose. Either way we would love to hear from you.

Some of the items are much older, and their precise use has been lost to history. Sophie is keen to hear your ideas about them. "I hope we can collaborate to generate some theories", she says. "I’m hoping to harness your user experience to improve our understanding of the chemistry collection, creating a vital resource for future historians and curators."

Each Monday for the next 12 weeks we will share a photo of a different piece of glassware – on social media and on this page – and ask for your insights, memories, and speculations.

Click on the buttons by each item below to send us your stories, and remember no contribution is too small!

Glass pestle and mortar, Europe, 1601–1700

Picture: © Science Museum

Made from Venetian style glass, this pestle and mortar looks like it has never been used. The pestle is used to pound and grind hard substances, spices and plants in the mortar for drug preparations. The set may have been owned by a pharmacist or apothecary or could have been made for decorative purposes. Pestles and mortars are usually made from materials such as marble or bronze.

Are there any examples when a glass mortar and pestle would be useful?

Picture: © Science Museum

Thousands of glass fermentation vessels like this one were used in Glaxo (now GlaxoSmithKline) laboratories to produce penicillin. The penicillium mould was grown on the surface of a liquid filled with all the nutrients it needed. This approach was superseded by the method of growing the mould within large industrial fermenters. The antibiotic was first used in the early 1940s and saved the lives of many soldiers during the Second World War.

Do chemists still uses these kinds of fermentation vessels in the pursuit of new antibiotics?

Picture: © Science Museum

Argon was discovered in 1894 by English chemist John William Strutt, most commonly known as Lord Rayleigh (1842–1919), and Scottish chemist William Ramsay (1852–1916), by the fractional distillation of liquid air.

Lord Rayleigh's method for the isolation of argon, based on an experiment of Henry Cavendish's. The gases are contained in a test-tube (A) standing over a large quantity of weak alkali (B), and the current is conveyed in wires insulated by U-shaped glass tubes (CC) passing through the liquid and round the mouth of the test-tube. The inner platinum ends (DD) of the wire receive a current from a battery of five Grove cells and a Ruhmkorff coil of medium size.

This famous experiment is well documented by historians of chemistry. Are these famous moments worth replicating? How do we isolate argon today?

This collection of 12 pieces of glassware made by Quickfit and Quartz Limited will be recognizable to many chemists. The Science Museum collects the everyday life of chemistry, as well as artefacts from the life and work of famous scientists and key experiments. In this photograph you can see the temporary number given to these objects when they arrived at the museum.

Modern manufacturing processes have produced laboratory glassware that is stronger, more chemically resistant, and usable at much higher temperatures than before. Standardisation of shapes, sizes and joints mean that elaborate apparatus can be assembled quickly and cheaply.

What do you love and hate about this standardised equipment? How much glassware still gets commissioned in your lab?

Picture: © Science Museum

A hydrometer is an instrument that measures the relative density of liquids. It is usually made of glass, and consists of a cylindrical stem and a bulb weighted with mercury or lead shot to make it float upright.

This ammonia hydrometer was used at Grimshaw Brothers and Sons Chemical Works in Clayton. It was made by Mothershead & Co, Manchester, and sold by Fred Jackson & Co Laboratory furnishers, Manchester. It is shown here with its original packaging.

What is the significance of having an ammonia hydrometer rather than one with the more traditional mercury or lead shot? Do chemists today use ammonia hydrometers?

Picture: © Science Museum

A eudiometer is designed to test the oxygen content of the air and is used today in chemistry. Atmospheric air and hydrogen are exploded over water by an electric spark and the rise of water in the tube gives an indication to the amount of oxygen present.

Eudiometers were taken across Europe by tour organisers looking for the best places for health resorts. Disease was thought to be caused by bad air and foul smells as a result of rotten rubbish, human waste and stagnant water. So clean air was considered essential in treating and preventing illness.

These eudiometers are said to have been used by the famous French chemist Marcellin Berthelot, noted for his developments and theorizing in thermochemistry and his synthesis of organic compounds.

What is your experience of using eudiometers?

Picture: © Science Museum

Invented by John Mervyn Nooth (1737–1828) in 1774, this device was made to reproduce natural spa water for medicinal uses. Following Joseph Priestley’s (1733–1804) experiments, carbon dioxide mixed with water was thought to be effective against many diseases such as scurvy. Nooth’s invention, which made carbon dioxide-rich water, was popular and sold in large numbers.

We know quite a lot about how this equipment was used and the man who used it, but is similar glassware used to make carbon dioxide-rich water today? Is this technique still in use? Do the chemists of today know how this would work or is this a lost art?

Picture: © Science Museum

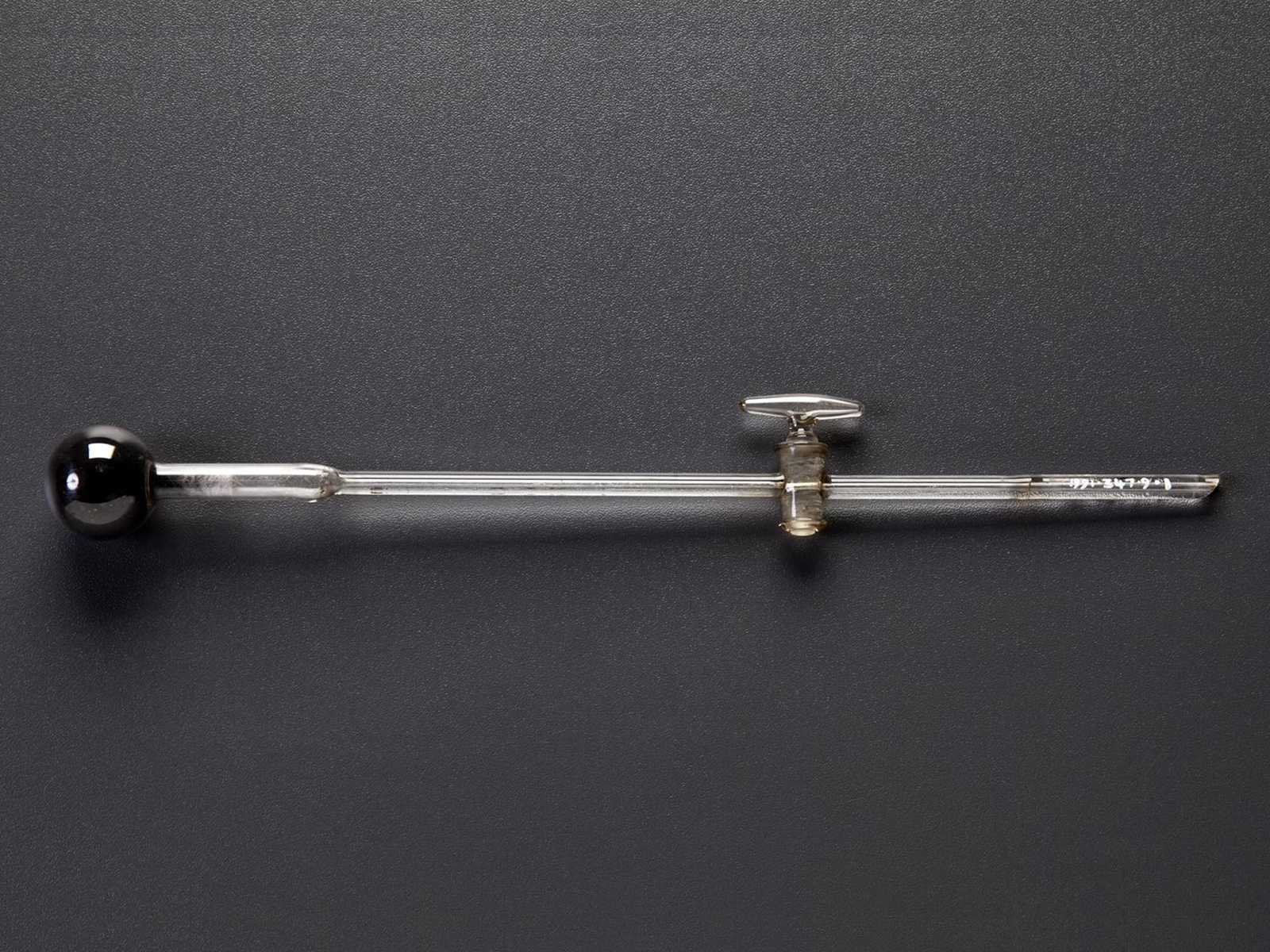

Image 1

This apparatus was used by Edward Frankland at Owens College chemistry laboratory during research on coal gas lighting, Manchester, c. 1855. It may have been used for exposing gas to charcoal. NB The end of the glassware is broken.

Why might we expose gases to charcoal? Is this still done today?

Picture: © Science Museum

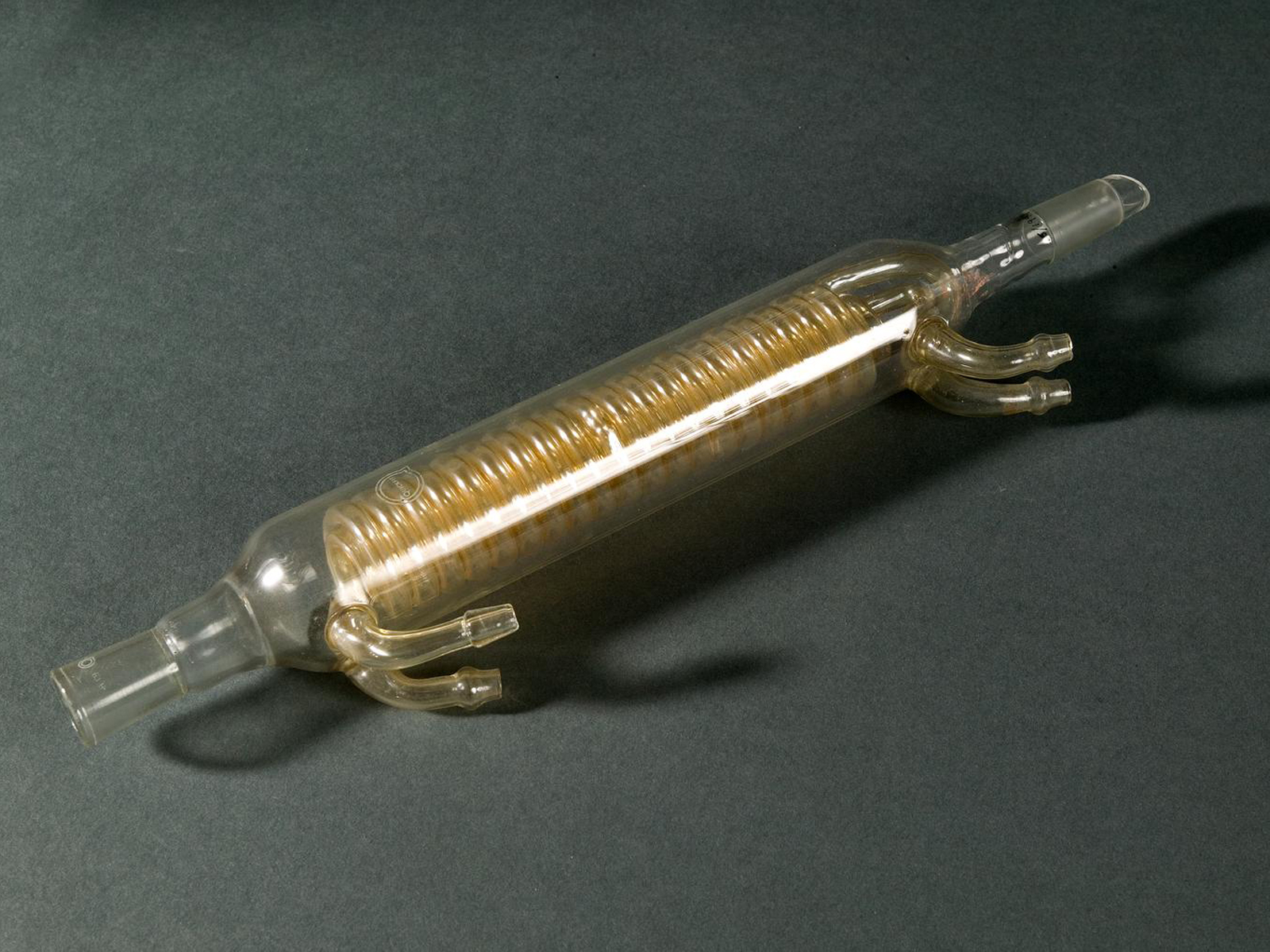

This piece of glassware was given to the collection by Zeneca Group PLC, prior to its merger with Astra AB, to form AstraZeneca.

Do you use these in your research? Can you tell us your experiences of using this type of spiral tubes?

Picture: © Science Museum

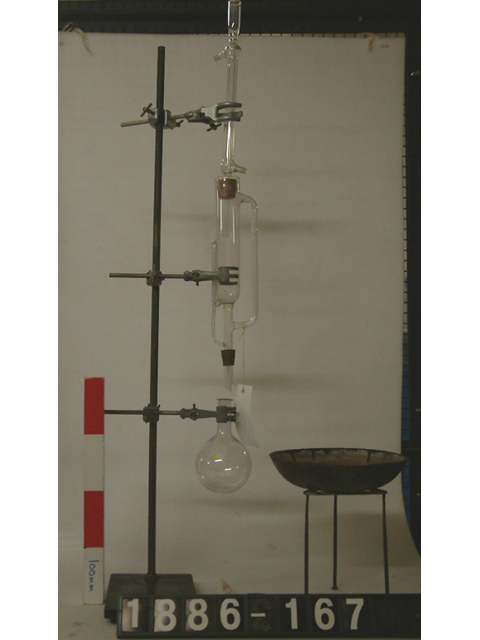

Soxhlet apparatus is still in use today. This particular set dates from 1885, and belonged to Townson and Mercer Limited.

Do you use Soxhlet apparatus? What is it like to do this kind of experimental work? Do you have any stories about it?

Picture: © Science Museum

This piece of glassware in from the Science Museum’s laboratory medicine collection. It’s probably English, and from around 1881–1920.

What do you think this might have been used for? Do you have a picture of something similar in your lab today?

Last year…

Below are the items we shared on social media in 2017. We have already received some messages from you, containing some great suggestions and interesting memories, which we plan to share at a later date. Do you have anything to add?

Picture: © Science Museum

This glassware is from the Fleet Street workshop of the famous Georgian instrument maker George Adams.

Currently the museum thinks it was apparatus for filling barometer tubes, can you think how it might have done this?

Picture: © Science Museum

This ornate twisted glass stirring rod was made by the Phoenix Glassworks in Bristol.

Is this just a flashy item for the privileged chemist or is there some utility in its elaborate shape?

Picture: © Science Museum

This retort with a tubular top opening dates from the 19th century and is of unknown origin and maker.

What kind of distillation would this have been used for?

Picture: © Science Museum

This is a Binks's burette, used most often in titrations, where control was provided by a thumb placed over a side tube. The Science Museum has examples from St Bartholomew’s Hospital and others from the dye manufactures Simpson and Maule.

When did this glassware stop being used? Do you remember doing titrations this way?