Electronic device amnesty

David Cole-Hamilton presents on the importance of preserving precious elements Picture: © Royal Society of Chemistry

This morning we hosted an event aimed at enabling London businesses to recycle more of their electronic waste.

The event was hosted by the Royal Society of Chemistry at Burlington House, and was organised by the Heart of London Business Alliance, in partnership with waste management company Paper Round.

The event opened with a talk by Professor David Cole-Hamilton, one of the masterminds behind the scarcity of the elements periodic table. He said that we are using up existing reserves of rare elements such as indium far too quickly, and that at the moment only 1% of indium and other rare elements is recycled.

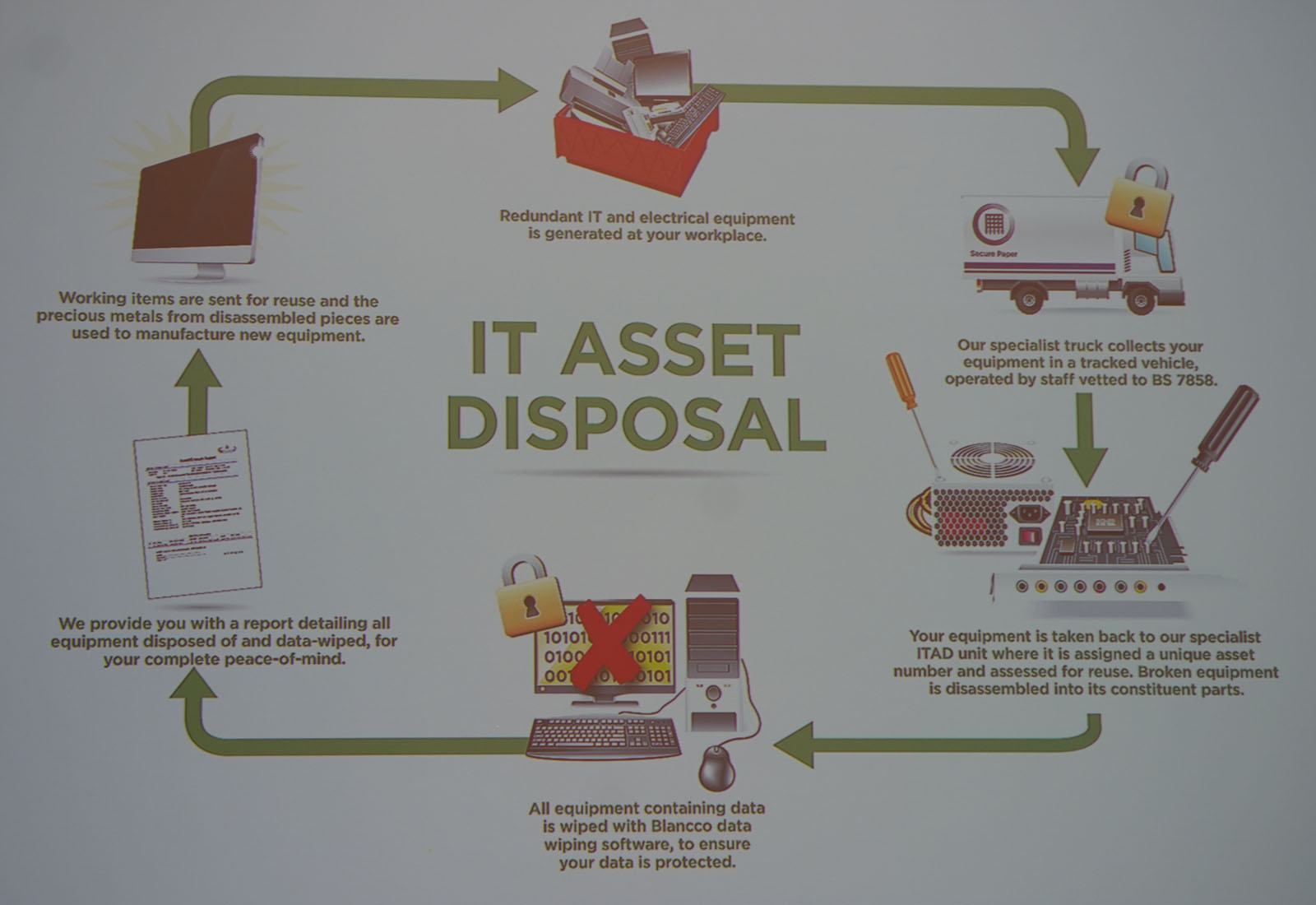

Ed Hubbard from Paper Round explained why it’s important to use a trusted partner to recycle electronic waste. "There are environmental consequences if you don’t recycle in the right way, there are social consequences if the items don’t end up in the right place – they could end up in Africa, where people are picking through waste without regulation, and there are financial impacts as well."

Ed’s talk explained that exporting electrical waste from the EU is illegal, and yet 350,000 tons of it are exported illegally every year. 64% of this ends up in Africa, where workers burn them to strip off the plastic and extract the metals. The burning process causes serious health problems for the workers and causes environmental damage.

Ed Hubbard spoke about the poor working conditions of people who strip electronic equipment for precious metals in Africa Picture: © Royal Society of Chemistry

Orlaith O’Byrne, also from Paper Round, highlighted the need to recycle batteries separately from other recyclables. "There are a few risks involved in putting batteries in mixed recycling bins", she said. "Mainly it's the risk of fire, so when we dispose of batteries of any kind, but especially lithium batteries - they can short circuit and lead to a fire. You can find separate collection points at supermarkets."

Picture: © Royal Society of Chemistry/Paper Round

Orlaith O'Byrne spoke about the methods used for recycling. Picture: © Royal Society of Chemistry

Orlaith also took us through what happens when electronic devices are taken to a Paper Round recycling plant – they are dismantled by hand in order to extract as many of the materials as possible, then the smaller components are sent to a specialist company for further recycling.

David Cole-Hamilton – who has been a leading voice in the campaign to preserve our precious elements – said that he had learned new things at the event. "I didn’t know very much about the process of dealing with the recycling. The fact is that it is difficult to find people who do recycling, unless you know who they are."

He also explained why it’s so important to recycle, even if we are able to find new reserves of precious metals.

Paper Round provided collection points for small electronics Picture: © Royal Society of Chemistry

"These metals are very widely dispersed. When it's concentrated you can get it out relatively cheaply, and when it's widely dispersed you can't, so it all becomes much more expensive. It's cheaper to get it from your phones than out of the ground."

The event included a collection point, and attendees were encouraged to drop off their small electricals for recycling. For bulk equipment Paper Round offered free collections to London businesses who attended the event.

Find out more about our campaign to save precious elements, including what you can do to help.