Without team it’s just work

Prizes and awards series

In the first of a new series, we hear from some of our prize and award winners about the importance of teamwork – from interdisciplinary research to international collaboration.

There is no single scientific discipline that can tackle the challenges that face society today. Scientific collaboration is essential to making new discoveries and developing solutions.

In our Science Horizons report, collaboration was cited by researchers as a key enabler of advances in the chemical sciences.

Using the words of our Prizes and Awards winners, we want to showcase the different ways in which collaboration happens. Through interdisciplinary research, international collaboration, and industry–academia partnerships.

Professor Teri Odom, winner of the 2020 Centenary Prize, says that interdisciplinary collaboration is key to good research. Picture:

Championing the 'inter' in interdisciplinary

The chemical sciences is highly interdisciplinary. Over 90% of the researchers we surveyed for Science Horizons had collaborated with people outside of their field.

The chemical sciences needs highly skilled disciplinary experts. It must also harness interdisciplinary approaches to answering questions and delivering solutions.

Working on complex problems that require multiple disciplines is what drives 2020 Centenary Prize winner Teri Odom.

"The most pressing societal problems that science can address are intrinsically complex," she says, "…integrating expertise from different disciplines is necessary just to even understand the problem, not to mention getting started."

Professor of chemistry at Northwestern University, Teri has a particular interest in nanolasers and their potential applications, like imaging diseased tissue.

"The research that has brought me the most satisfaction has usually involved two or more collaborators, where the big result wouldn’t have been possible without everyone’s distinct contributions," says Teri.

"Learning the language of different fields – while rooted in chemistry – will enable multiple, unique convergent approaches to solve difficult problems and open new areas of science."

Based at the University of São Paulo, Norberto Lopes’ interest lies in the chemical dynamics of the natural world. The rich ecology of his native Brazil inspired Norberto to study the biological activity of plants in the Amazon and their use by indigenous people from remote regions.

This year, Norberto received the Jeremy Knowles Award, which recognises the importance of inter- and multi-disciplinary research between chemistry and the life sciences.

"Teamwork is important in science… I don’t know how to work differently," says Norberto. "My whole life I worked in groups with biologists, chemists, pharmacists and doctors."

"In the area I have chosen, there are no answers to the challenges presented by nature without group and interdisciplinary work," Norberto says.

Professor Richard Catlow, winner of the 2020 Faraday Lectureship Prize, says that science is global. Picture:

Working beyond borders

The advancement of science is a global endeavour, and the COVID-19 pandemic is a powerful example. It has galvanised the global scientific community into urgent action to understand, treat and prevent the ongoing spread of the virus.

In our survey for Science Horizons, 85% of researchers said they had been involved in an international collaboration within the past five years.

"International collaboration is essential," says Richard Catlow, whose work in computational technology earned him the 2020 Faraday Lectureship Prize. "Science is global and thrives when people from different cultures and intellectual backgrounds exchange ideas and collaborate."

"Scientists, especially early in their careers, deepen their knowledge and experience by working with others from around the world," he says.

2020 Harrison-Meldola Memorial Prize winner, Dr Thomas Bennett, worked overseas at the start of his career. Picture:

That’s certainly true for Thomas Bennett, who took full advantage of the opportunity to work overseas at the beginning of his research career. Thomas leads a research group at the Department of Materials Science and Metallurgy at the University of Cambridge. This year he was awarded the Harrison-Meldola Memorial Prize.

"Research stays at the University of Kyoto and University of Canterbury New Zealand were both incredible opportunities – from the extremely warm welcome, to discussing interdisciplinary science, to learning about different cultures and experiencing life from a new perspective," says Thomas. "I think that the best science always arises from broader perspectives."

Dr Mark Crimmin works in a diverse team to solve problems involving fluorocarbons. Picture:

A magnet for talent

No matter where they are in the world, the mobility of researchers is vital for collaboration.

Mark Crimmin is reader in organometallic chemistry at Imperial College London. His team focuses on developing new ways to recycle and repurpose environmentally persistent fluorocarbons. This year he received the Chemistry of Transition Metals Award.

"Success really depends on teamwork. Diverse teams that include people with different perspectives and different training are the most successful," says Mark.

"Imperial College, being at the heart of London, is really an excellent place to carry out research. We are lucky enough to attract really great people from across the world with diverse backgrounds and this makes it a really special place to work."

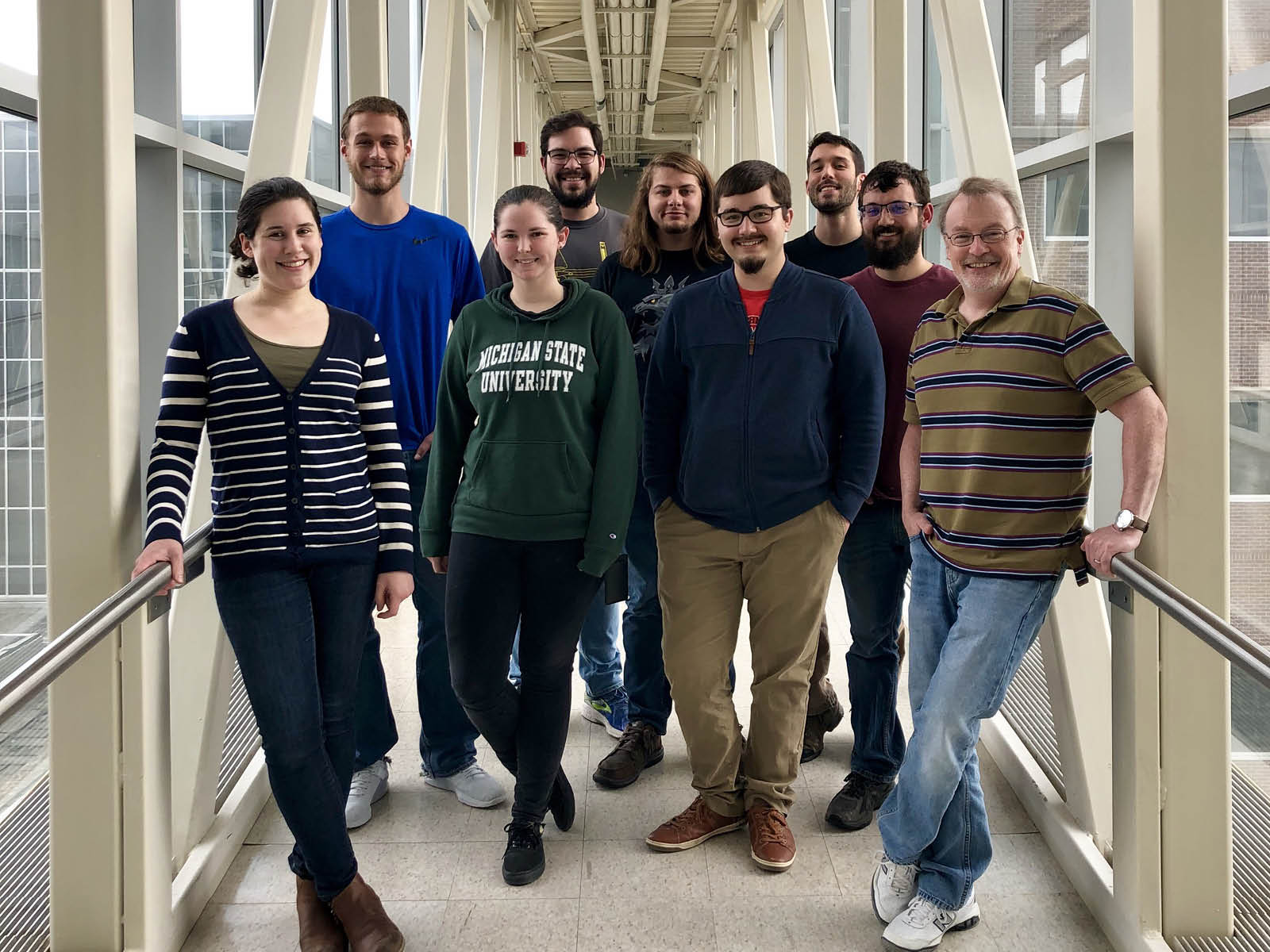

Professor Jim McCusker and his research group are always keen to work with other groups. Picture:

Jim McCusker is based at Michigan State University and received the Chemical Dynamics Award this year.

His research group is focused on understanding what happens at the molecular level when something absorbs energy in the form of light. Their goal is to help lay the foundation for advances in areas like fuel generation, electricity, and the creation of new classes of pharmaceuticals.

"Science is one of the few disciplines that truly knows no borders. In my research group, we tend to develop whatever methodology that we need in order to pursue our scientific goals, but if there is an individual or research group somewhere in the world who is the best at something that we feel will advance our science, well, why not work with and learn from the best?"

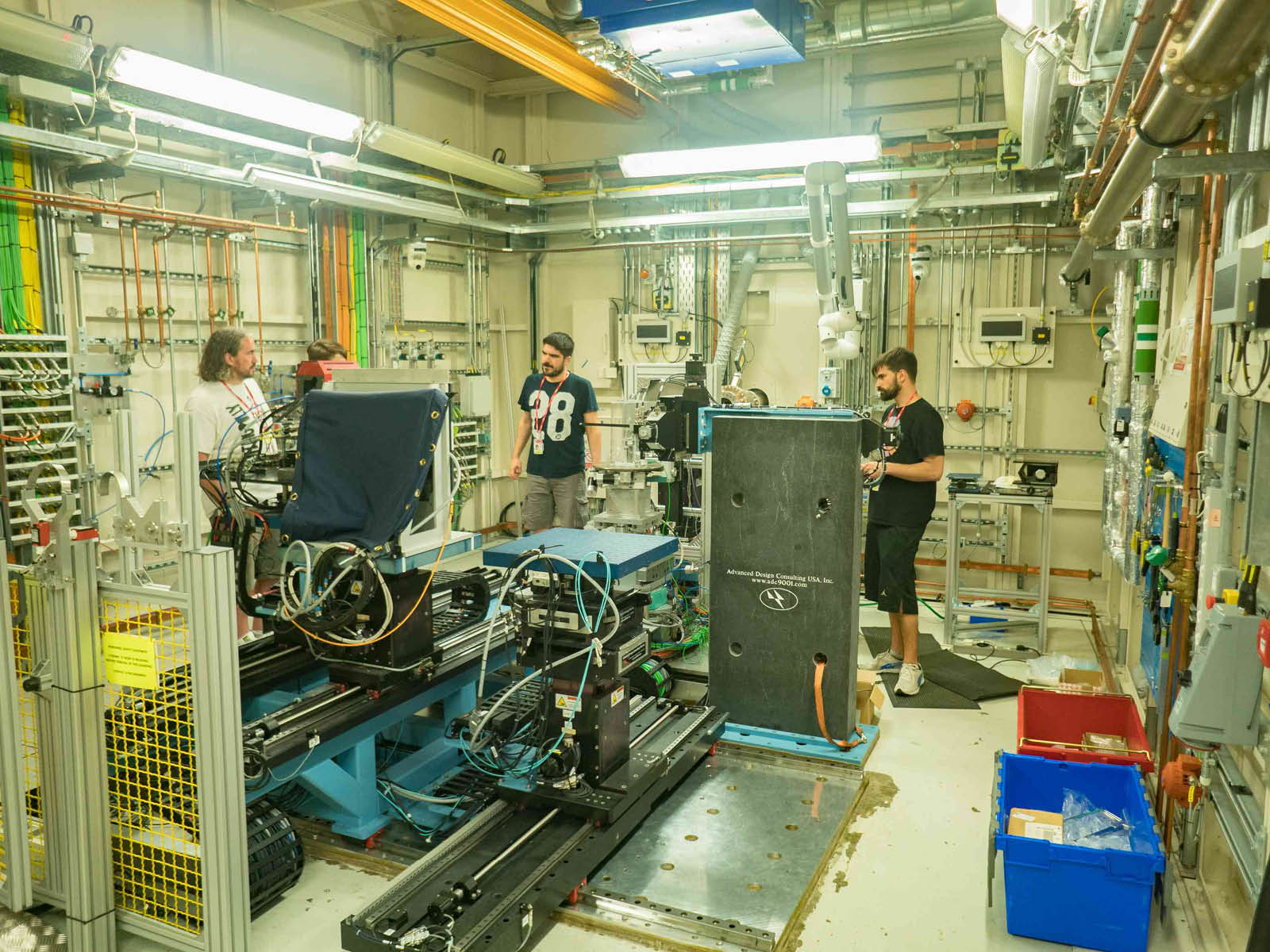

The DISTINCTIVE consortium includes ten universities and three industry partners. Picture:

Creating a culture of collaboration

Increasingly, companies have turned to universities to carry out early-stage research, and to access scientific talent. Universities have taken advantage of financial support and the ability to commercialise their research outputs.

The DISTINCTIVE consortium is a case in point, and winner of the 2020 Industry-Academic Collaboration Award.

Led by Mike Fairweather from Leeds University, the consortium includes ten universities and three industry partners, focused on nuclear decommissioning and waste management.

"The complexities of nuclear decommissioning and waste management make teamwork and collaboration essential," he says. "Ideas and critical thinking are developed from multiple perspectives, allowing greater creativity and the synthesis of novel, synergistic and effective solutions that are beyond the capability of a single discipline."

Professor Chris Abell is working as part of a large team to set up a COVID-19 testing centre. Picture:

Chris Abell is pro-vice chancellor for research and professor of chemistry at the University of Cambridge. He’s currently working as part of a team of scientists from AstraZeneca and GSK to set up a high throughput COVID-19 testing centre at the university.

"This is an astonishing project, bringing together chemists, biologists, and virologists, with experts in automation and IT," Chris says. "What we are achieving is exciting and important – and would be impossible without teamwork and trust."

Winner of this year’s Interdisciplinary Prize, Chris’s research has given him exposure to many other disciplines. Molecular biology, structural biology, computational chemistry, material science, plant science, and nanotechnology have all helped Chris to achieve specific goals in his work.

Fostering faster innovation

The Royal Society of Chemistry has a long history of bringing the chemistry-using community together.

One of our latest programmes is Synergy, where we bring together businesses working in different industries to tackle complex chemistry-based topics. So far, we’ve focused on reducing waste in the formulations industry, and preventing corrosion via the use of non-metallic materials in various ways. The topics are driven by industry and suggestions can be submitted via our website.

Recognising teamwork

For over 150 years, the Royal Society of Chemistry has recognised excellence in the chemical sciences.

Traditionally, the focus of recognition has been on individuals. And, while individual recognition has important purposes, teams and collaborations are integral to scientific endeavour.

Our Prizes and Awards programme has changed and broadened with the advancement of chemistry as a discipline and its applications.

In our report, Rethinking Recognition, we set out how recognition in the 21st century must reflect the many types of excellence that are crucial for modern science.

For example, we will place more emphasis on great science, not just top professors. We want to recognise that teams, technicians, and multidisciplinary collaborations enable advances in the chemical sciences.

We will continue to award and celebrate the diversity of ways in which people contribute to science and society.

Want to find out more?

- Visit our winner gallery to explore more of our 2020 Prizes and Awards winners.

- Read our Science Horizons report to learn more about emerging trends and priorities in scientific research.

- Get involved in Synergy, our collaborative programme for industry.

- Explore how we are re-thinking recognition to make our science prizes fit for the modern world.

- Apply for one of our Researcher Mobility Grants – up to £5,000 is available for collaboration with overseas or UK organisations.